To date we know very little about the specific circumstances and factors that might impact women’s involvement in the transition to clean energy. Fortunately, this topic is slowly starting to attract attention in research and policy circles.

Results of existing studies show that when striving for energy democracy, we must not overlook an important discrepancy between the roles women play as energy consumers, entrepreneurs, employees, and policy makers.

Women think differently about energy

Women represent around a half of the population of the EU. However, there are reasons to believe they consume proportionally much more energy. The current global labour force participation rate for women is close to 49%, while for men is 75%, states the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

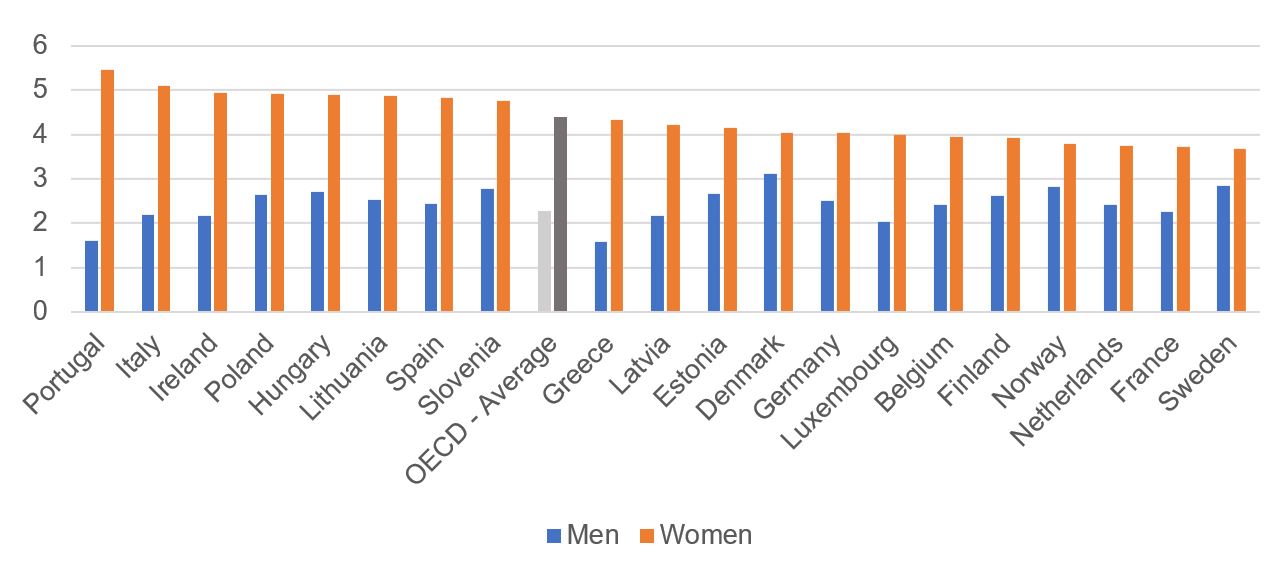

This means that women spend more time at home, managing most of home energy consumption, from heating to powering of household devices (e.g. washing machines, vacuum cleaners, dishwashers). They perform many more household chores than men, spending 4.5 per day on average doing so (vs 2.3 hours for men), shows data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Image: Time spent (hours per day) in unpaid work by women in Europe - Source: OECD.stats

From the ecological point of view, it might be good news, since women seem to be more energy efficient than men. According to surveys reported by OECD “women tend to be more sustainable consumers and sensitive to ecological, environmental and health concerns. They are more likely to recycle, minimise wastage and buy organic food and eco-labelled products. They also place a higher value on energy-efficient transport and in general are more likely to use public transport than men (…). Women can therefore be key actors in shifting consumption towards more sustainable patterns. In this regard, public policies and new approaches to influence consumption decisions, such as behavioural insights should take into consideration a gender perspective.”

Similar results were obtained from a global study Consumer Life conducted by GfK in 2019: significantly more European women than men value environmentally friendly cars (49% women vs 43% men).

Eleanor Denny, an associate professor of Economics at Trinity College Dublin, the University of Dublin, confirms: “Under the EU project CONSEED, we conducted surveys on attitudes to energy efficiency when making purchasing decisions for appliances, properties and cars. Females were more likely than males to say that energy efficiency is very important in that decision. We don’t have data on the gender breakdown of actual purchasing decisions, but certainly the stated opinion was that women care more.”

Denny is also collaborating with the EU project SocialRES, which studies socio-economic, cultural, political and gender factors that influence consumers in the energy system. It focuses on members of energy cooperatives, aggregators and crowdfunding platforms. Data are collected from surveys conducted in seven countries: Germany, France, Spain, Portugal, the UK, Croatia, Romania.

“We want to understand what is motivating people to engage in social energy initiatives and to become early adopters, in order to estimate if the projects could be scaled up and replicated elsewhere. We don’t have specific results yet, since the surveys are ongoing, but it’s going to be exciting,” she says.

One of the aims of the project is to promote new ways of collaboration between energy cooperatives, aggregators and crowdfunding platforms. This is to boost decentralised participatory energy systems and democracy in tomorrow's renewable energy market. In this context the collection of data about the role of gender in social innovation in the energy sector, currently unknown, is quite interesting.

Barriers to women’s engagement in the energy sector

It is critical to directly engage women, as primary users of energy in the household, in renewable energy projects. However, they face a range of barriers. Among these, 72% of respondents in a survey conducted by the International Renewable Energy Acency (IRENA) cited social and cultural norms, which are conditioned by traditional power hierarchies. As an example, men often make the purchasing decisions within the household.

Other important barriers are a lack of gender-sensitive policies and scarce training opportunities: they were mentioned by 49% and 41% of respondents respectively. Allotting a significant amount of time to household work, females have less time for other activities, including renewable energy projects. At the same time, social impact assessments, consultations and policy development often do not adequately address women as stakeholders, together with other marginalised groups.

Females also have insufficient access to information and training, both technical (involving installation, operation and maintenance), and business-related. “To encourage women to adopt renewable solutions, we need to ensure they have information about the possibilities of the installations required. One-stop-shop services, where they can get the ‘full package’ assistance, would help them overcome technical difficulties,” commented Ksenia Petrichenko, Economic Affairs officer at United Nations ESCAP.

Underutilised female workforce

Europe loses EUR 370 billion a year due to the gender employment gap, stated the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC), a EU advisory body comprising representatives of workers' and employers' organisations and other interest groups.

Women account for a mere 26% of the total workforce in the energy sector. Their representation at higher levels in the organisation is even lower: 23% of managers and 17% of board members are female on average, as a recent study of Boston Consulting Group and Women in Energy Association shows.

“Indeed, the energy sector has traditionally been male-dominated, and this remains so, especially on positions requiring physical work,” opined Irina Volkova, deputy director of the Institute of Pricing and Regulation of Natural Monopolies in the Higher School of Economics.

Women represented on average 32% of the workforce in the renewable energy sector in 2018. This is higher than in the traditional energy sector, but still lower than their share across the EU economy (46%).

“The proportion of women is unacceptably small, and this leads to a noticeable limitation in decision-making both within energy companies and at the state level: the lack of diversity in the managerial staff (both gender and age) narrows the perspective, and very often leads to the adoption of traditional, but ineffective solutions,” stressed Tatiana Mitrova, senior research fellow at Oxford Institute for Energy Studies and director of Energy Centre at Moscow School of Management SKOLKOVO.

“In many cases, the low proportion of women in top positions is dictated by just this: they simply do not have energy, time or desire to move up the career ladder. The main solution to this problem is a change in public attitude, in both men and women: a transition to more equal, partnership relations with a more adequate division of responsibilities at home and in childcare.”

Globally, women represent only 6% of ministerial positions responsible for national energy policies and programmes. This leads to a failure to recognise their specific needs and to address barriers for participation in the energy transition. “Policies supporting women during and after their pregnancy (equal maternity and paternity leave, affordable day care and education for children, etc.) are crucial. They facilitate women's career development without compromising on a work–family life balance,” added UN officer Petrichenko.

“I think quotas would be a good start. In the future, as more adequate proportions are achieved, quotas can be eliminated, but in the beginning it would be extremely difficult without them,” says Mitrova. This approach has already been put into practice by more than a third of European states. In the 2019 EU parliament elections 11 states had gender quotas (vs 8 states in previous 2014 elections).

To sum up, energy policy affects men and women differently. Females face major barriers in shifting from energy efficiency-oriented consumers to clean energy entrepreneurs, employees, and especially policy-makers. We’re currently on our way to finding out more about these obstacles to identify optimal solutions.